Jerusalem

THE INDEPENDENT Thursday 15 March 2012

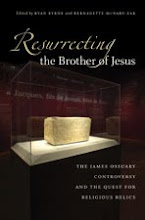

A burial box inscribed “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” was reprieved from the scrapheap of history yesterday when a Jerusalem judge exonerated the Israeli antiquities collector accused of forging it.

The verdict, delivered by Judge Aharon Farkash in a tiny, crowded courtroom in the Jerusalem District Courthouse, ended a nine-year ordeal for the accused, Oded Golan, 60, but it will do little to extinguish the decade-long scientific controversy over the authenticity of the limestone box, which has raged since it was first displayed to the public at the Royal Ontario Museum in 2002.

If genuine, the burial box, or ossuary, is the first physical artefact yet discovered that might be connected with the family of the historical Jesus Christ.

Mr Golan had been accused of adding the second half of the inscription linking it to Jesus, and then fabricating the patina, the bio-organic coating that adheres to ancient objects, to pass it off as genuine.

But Judge Farkash said the prosecution had failed to prove any of the serious charges against Golan and acquitted him on all but three minor charges of illegal antiquities dealing and possession of stolen antiquities. Robert Deutsch, a codefendant, was acquitted on all charges.

“The prosecution failed to prove beyond all reasonable doubt what was stated in the indictment: that the ossuary is a forgery and that Mr Golan or someone acting on his behalf forged it,” Judge Farkash told the court, summarizing his 475-page verdict.

He noted that it was the first time a criminal court had been asked to rule in a case of antiquities forgery.

The spectacular collapse of the trial, nine years after Mr Golan was arrested and thousands of items were seized from his home, office and warehouses in Tel Aviv, was a severe blow to the Israeli police and Israel Antiquities Authority, who claimed they had exposed “the tip of the iceberg” of an international conspiracy selling fake artefacts to collectors and museums worldwide.

But Judge Farkash acknowledged that the collapse of the criminal trial did not signal the end of the scientific debate over the authenticity of the ossuary.

“This is not to say that the inscription on the ossuary is true and authentic and was written 2,000 years ago,” he said. “We can expect this matter to continue to be researched in the archaeological and scientific worlds and only the future will tell. Moreover, it has not been proved in any way that the words ‘brother of Jesus’ definitely refer to the Jesus who appears in Christian writings."

“The indictment... accused Golan of faking antiques in different ways. For certain items, I decided that it was not proven, as required in criminal law, that they were fake. But there is nothing in these findings which necessarily proves that the items were authentic,” said the judge.

“All that was determined was that the means, the tools and the science available at present, along with the experts who testified, was not enough to prove the alleged fraud beyond reasonable doubt,” he said.

Judge Farkash was particularly scathing about tests carried out by the Israel police forensics laboratory which, he said, had probably contaminated the ossuary, making it impossible to carry out further scientific tests on the inscription.

Mr Golan, who was accompanied to court by his elderly parents, said he was “delighted at the complete and total acquittal I have received here today.”

“We brought experts from all over the world who testified that the inscriptions on the items that were suspected of being fakes are completely authentic,” he said.

“What we tried to do here has set an international precedent,” said Prosecutor Dan Bahat. “This is the first time someone has brought the issue of antiquities forgery before a court.”

In December 2004, Golan and four other defendants were charged with 18 separate counts of forgery, fraud and obtaining money by deception. They were accused of faking not just the James ossuary, but a huge number of antiquities including a stone tablet recording repairs by King Joash to Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, an inscribed decanter apparently used in the Temple service, ancient seals, inscribed pottery and dozens of other items.

“We have grounds to believe that there are many more fake artefacts circulating, both in private collections and museums in Israel and abroad that we haven’t found yet,” Jerusalem police chief Shaul Naim said at the time.

“I believe we have revealed only the tip of the iceberg. This industry circles the world, involving millions of dollars,” said IAA director Shuka Dorfman. “Beside this, Indiana Jones looks small.”

In autumn 2005, the trial opened in the Jerusalem District Court of Judge Aharon Farkash. Mr Golan was indicted on 15 of the 18 counts, accused of a total of 44 separate crimes, the most serious of which carries a seven-year sentence. He spent the first 18 months under house arrest.

In sharp contrast to the worldwide publicity that accompanied the discovery of the ossuary and Mr Golan’s subsequent arrest, the trial attracted little interest. For five years, hearings were conducted in a tiny courtroom with just a dozen people in attendance, including only one reporter.

When Judge Farkash eventually retired to consider his verdict in October 2010, charges against two defendants had been dropped and one more had been convicted and sentenced on a minor count of deception. Farkash had presided over 116 sessions, heard 133 witnesses, examined 200 exhibits – many of them entire books and scholarly papers – and heard nearly 12,000 pages of witness testimony. The prosecution summation alone ran to 653 pages.

Throughout the lengthy proceedings, Judge Farkash kept returning to two central points: whether the items under suspicion were fakes, and whether the defendants or someone acting on their behalf had faked them.

The prosecution presented three main arguments to prove that Golan had faked the “brother of Jesus” part of the ossuary inscription: scholarly, scientific and circumstantial.

The scholarly evidence was provided by experts in palaeography and ancient inscriptions who testified that the words “brother of Jesus” appeared to have been inscribed by a different hand and were highly unusual in ossuaries from the period. The scientific evidence derived from an examination of the patina that showed it had a different oxygen isotope composition to the other letters and the surface of the box. The circumstantial evidence rested on tools, soil samples and half-finished objects seized from Golan’s home and warehouses that appeared to be the raw materials for faking antiquities and covering them with a false patina.

But what began as a worldwide conspiracy with more anticipated arrests and certain convictions slowly began to unravel. Despite the confident predictions, nobody else was arrested and no more fakes were found. Not a single forgery emerged from a museum. The “tip of the iceberg” was melting.

In court, lawyers for Mr Golan and Robert Deutsch, his codefendant, produced equally eminent experts to challenge the findings of each prosecution witness. Sometimes the opposing witnesses came from the very same university campus.

Professor Yuval Goren of Tel Aviv University, a member of the IAA experts’ committee and the main prosecution witness, originally testified that the patina in the word “Jesus” could not have formed under natural conditions and must be a later addition. Under intense cross-examination, Professor Goren was forced to change his original testimony, agreeing with defence experts that there was indeed authentic patina in a groove of the final letter. Professor Goren suggested this was because an “ancient groove” had been incorporated by the forger into the newly-carved word.

“Scientific debates should be discussed and resolved in peer-reviewed literature and scientific conferences, not in court,” said Professor Aldo Shemesh, an isotope expert at the Weizmann Institute and expert defence witness, echoing the majority view among the long procession of world-renowned professors from Israel, America and Europe who joined the five-year progress through the modest courtroom.

Mr Golan, 60, made an unlikely criminal. One of Israel’s leading collectors of antiquities, his Tel Aviv apartment resembles a museum, lined with glass-fronted cabinets displaying hundreds of ancient items. Hundreds more are stored in several warehouses. He was born into the city elite. His grandfather founded one of Israel’s major insurance companies and the family purchased land in Israel’s early years that is now worth millions. His mother, now retired, is a world-renowned biochemist and his brother, who died during the trial, was a leading Israeli publisher.

Mr Golan trained as an engineer and became a serial entrepreneur with successful businesses in travel, architectural seminars and educational software. He is also an accomplished photographer and plays concert-level classical piano on the white baby grand in his living room. If he is guilty of masterminding an international forgery ring, it’s not because he needs the money.

“I never faked any antiquity,” said Mr Golan, who thinks he bought the ossuary in the 1980s from a dealer in the Old City of Jerusalem. A photograph he produced at the trial, dated by an FBI expert to the 1980s, shows the ossuary complete with inscription on the balcony outside his bedroom.

“I cannot guarantee that it belonged to the brother of Jesus Christ but it’s definitely ancient. I have no doubt about it,” he said.

A guilty verdict would have convinced most observers that the inscription is fake, and therefore historically worthless. But even though Mr Golan was found innocent, many of the experts will continue to doubt the authenticity of the James ossuary.

“My tests showed that the patina coating the ossuary was more or less homogenous, but the patina coating the inscription was completely different,” said Professor Goren.

“The entire patina that coated the inscription was obviously not the same as the patina coating the rest of the ossuary, which is highly suspicious… Somebody created or simulated an authentic patina but in modern times,” he insisted.

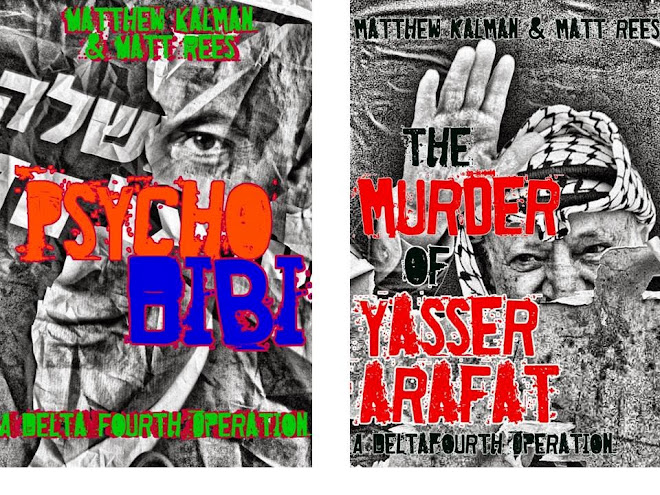

Matthew Kalman is editor in chief of The Jerusalem Report.